Vandana Borse, hailing from Jalgaon, is exhausted from rounds to three hospitals in a day. Her son Prem, 7, underwent surgery for a brain tumour at JJ Hospital in Mumbai in early March. She recounts a two-month-long ordeal starting in January when Prem – a cheerful child, fond of cricket – started showing symptoms like headaches and vomiting. An MRI scan at a local hospital in Jalgaon found that he had a brain tumour. After their doctor recommended a doctor in JJ Hospital for surgery, they made the trip to Mumbai.

What they thought was a two-week procedure stretched to almost one-and-a-half months. After the surgery, Vandana was advised to get a second opinion from Tata Memorial Hospital, while the routine scans happened at Nair Hospital since they were cheaper there.

The family’s only source of income is their marigold farm which they work on themselves. They had already spent over Rs 50,000 on Prem’s treatment and medication and had to additionally pay caretakers to look after their farm in their absence.

Renting a room in any nearby hotel or dormitory in the city costs a minimum of Rs 500 per day, an expense that most families like the Borses can’t cover. Real estate prices in Mumbai are unaffordable and temporary accomodations in their price range are hand to find.

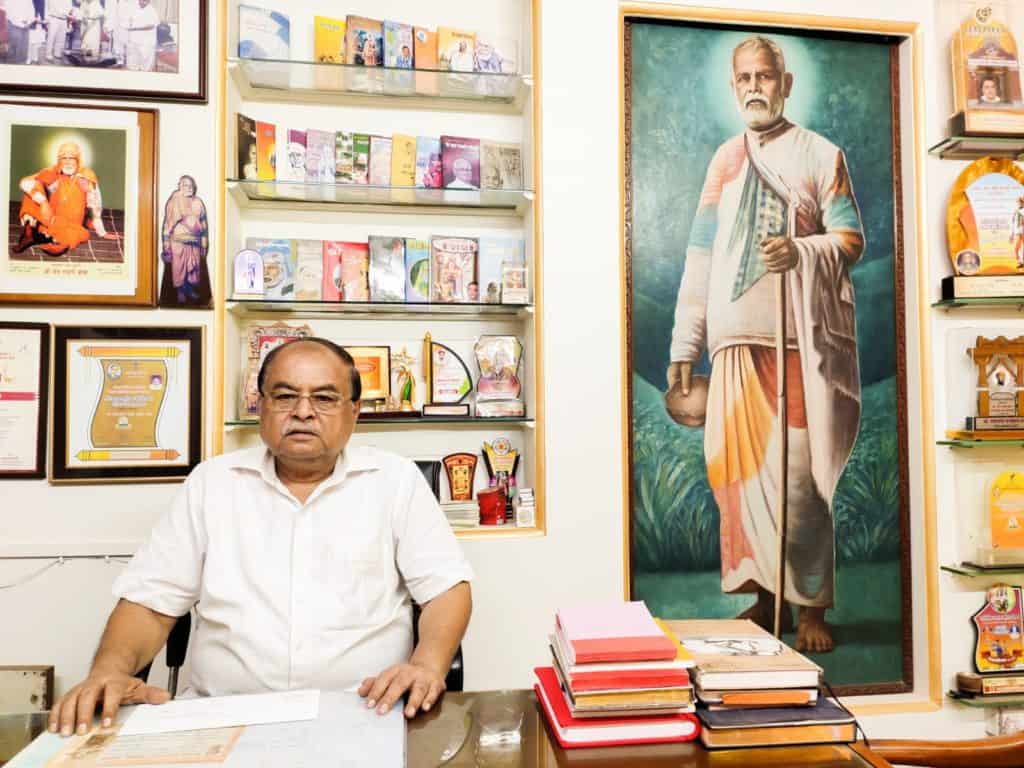

The family has been living in the St. Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala through Prem’s treatment. “They provide affordable accommodation and food in a city like Mumbai,” Vandana said, as she pointed at the Dharamshala’s Trustee, Eknath Shinde. “Without this room, our entire expenditure would have doubled,” she added.

A gap in Mumbai’s healthcare system

According to an official in the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), over 30% of people in Mumbai’s government hospitals come from rural areas of Maharashtra and other states. In March, photos of overcrowded wards in Nair Hospital went viral, displaying patients assigned to the floors due to the lack of beds in the general ward. This situation only worsens in the monsoon season, when patients cannot wait around in the premises. In another similar case, in January 2020, the Tata Memorial Hospital had to make space for its cancer patients and their families under the Hindmata bridge.

A glaring gap in Mumbai’s healthcare system befalls patients who travel to the city for quality treatment. While the issue of the lack of beds can be resolved at a hospital level, Dharamshalas and care homes alike are fulfilling a greater need – housing families of patients.

The Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala, the Ernest Borges Memorial Home, Mafatlal Mohanlal Mehta Dharamshala and the Nana Palkar Dharamshala all provide temporary accommodation for families of patients undergoing treatment in Mumbai’s hospitals at an affordable cost.

In the Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala, renting a private room costs Rs 60 per day, and Rs 30 if you choose to live in the common halls, of which they have 3. They provide healthy breakfast, lunch, dinner and tea for only Rs 35 per day. Currently, they have 51 private rooms and can accommodate up to 125 people in their Dharamshala. There is a common toilet on each floor of the building

In the Nana Palkar Home in Parel, they have 38 rooms in total. Each room has a private washroom and can accommodate up to four people – two patients and two family members. Here a maximum of 150 people can be housed at any given time.

In the Nana Palkar Home, rooms are provided to families free of charge if they are being treated in a government hospital. If they’re undergoing treatment in a private hospital, Rs 100 is charged for the room per day. Breakfast and lunch/dinner is provided at Rs 5 and Rs 10 respectively. They also get a grant from the Annapurna Yojana Scheme, which provides a certain amount of food grains per person per month – usually 10kgs for senior citizens.

These spaces also nurture a community for families going through difficult periods, by surrounding them with other families in similar situations. “I’ve spent 5 months here, and the people here are very helpful. I have even made friends with other residents here after day-long treatments,” said Sheetal Ranidelhia, from Bihar, who is a resident of 5 months in the Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala. Such companionship offers emotional support for those far away from their native homes.

Read more: Money allocated, plans made and yet public toilets are not built in Mumbai. Here’s why.

A history of care

The Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala was built in 1955 by St. Ghadge Maharaj after witnessing the state of patients and families on the JJ Hospital premises. Hospital officials would occasionally let them on lawns and hospital corridors, but without the proper care or acknowledgement, families were left distraught.

Initially, 12 rooms were built with the help of philanthropic funding, but in 1978, with the help of a generous donation from Mafatlal Mohanlal Mehta and his family, they renovated the place to how it looks today – with 51 rooms, 3 common halls, a canteen area, a quadrangle for assembly and a temple in the premises.

While they’ve provided for families of all patients, they’ve especially cared for cancer patients and their kin. “We recognise that there is a critical shortage of good doctors and Oncology Departments in government hospitals in villages. 80% of our residents have a family member going through cancer treatment,” said Eknath Thakur, the Dharamshala’s Trustee, and St. Ghadge Maharaj’s sevak.

Thakur has been running the place for over 40 years, with the help of private philanthropic funding and donations from trusts, which he chose to keep anonymous. “Many individuals donate to us on their birthdays, anniversaries, and death anniversaries of their close relatives,” he added. Their motto ‘Bhooke ko khana do, pyase ko paani’, meaning ‘provide food to the hungry, and water to the thirsty’, emphasises serving those in need. The Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala gets no government funding.

Similarly, In 1968, a year after the Death of Nana Palkar, a staunch member of the Rashtriya Seva Sangathan (RSS), the Nana Palkar Home was built in Parel. Nana Palkar served the sick and poor his whole life, sometimes providing them space in his own house. Inspired by his initiatives, his co-workers in the RSS, Madhavrao Paralkar, Narayan Bhide and a few more colleagues decided to build the Nana Palkar home to help families of patients in dire financial situations.

The Nana Palkar Smruti Samiti, a trust, was established in 1968 when a home with two rooms was built. They soon received recognition from the BMC, and a plot was allotted to them in Parel, where a 7 storey building was built in 1997. Currently, the building is 10 floors and has 38 rooms along with a dialysis centre and a diagnostic lab.

Lack of space and funds

A common challenge in most of the spaces seems to be funding. “Our team of Trustees make sure funding is always coming in, but it was difficult to keep the place running smoothly all 365 days. We’d see some days when funding was scarce,” said Swati Angre, an Assistant Administrative Officer of the Nana Palkar Smruti Samiti trust.

However, since 2017, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds have brought some respite. Corporates donate to a common CSR fund which is then distributed to NGOs and trusts undertaking social welfare activities, to aid their everyday operations. The Ministry of Corporate Affairs is in charge of the distribution of the funds. “The registration procedure is long and tedious, and funds are usually delayed. But it covers a big chunk of our expenses,” said Swati.

Despite some funding, there is still a lack of space, owing to the large influx of patients from rural areas. Since most patients, like cancer patients, need long-term accommodation, it is difficult, sometimes, to provide for all patients and families in need. Nana Palkar Home, where 99% of the patients are cancer patients undergoing treatment in KEM and Tata Memorial Hospital, has an upper limit of 1 month for guests, to be able to make room for others. At the end of the month, guests may re-apply for their stay but will be assigned a room after the waiting period. While this is an ideal solution to maintain a rotation of guests and allow more families accommodation, what is required is funding for more spaces like these, to reduce waiting periods.

Dharamshalas in Mumbai:

- Nana Palkar Smruti Samiti

158, Rugna Seva Sadan,

Rugna Seva Sadan Marg, Parel,

Mumbai – 400 012

Tel. No. : 022 24102167 Email : nanapalkar15@aartiaggarwalgupta - St. Ghadge Maharaj Dharamshala

JJ Hospital compound, Gate no. 14

Byculla, Mumbai – 400008

Tel. No. : 022 23790738 - Ernest Borges Memorial Home

Kala Nagar, Bandra East, Mumbai,

Maharashtra 400051

Tel. No. : 022 – 2659 1404

According to Mathew George, a public health professor at Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), the Dharamshalas and care homes are only a temporary solution for what is a larger issue at hand. “Ideally, we should have quality tertiary care in all districts of Maharashtra, but this is not the case. Problem isn’t with rural areas alone, Mumbai largely has only government infrastructure for primary and tertiary care, while secondary care has been left for the private sector to profit from,” he adds.