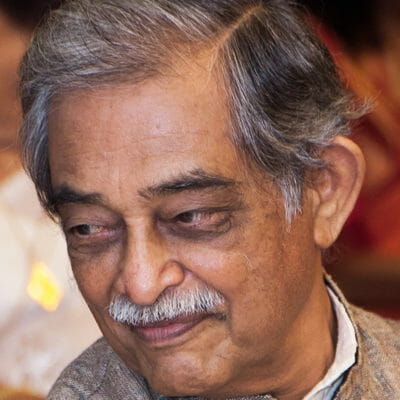

There are few people more well-versed about urban planning in Mumbai than Shirish Patel.

The civil engineer and urban planner has been around for decades, watching the island city grow into the suburbs. He has witnessed the skyward trajectory of infrastructure in the city and at the opposite spectrum, degradation, crumbling under the Rent Control Act, Urban Land Ceiling and Regulation Act (ULCRA), and over dependence on floor space index (FSI) rules. He designed India’s first flyover, at Kemps Corner. And then, along with Charles Correa, he was the one of the first to suggest and draft a plan for New Bombay, the satellite city to Mumbai.

Shirish continues to have a prolific work life; filing PILs challenging the manner of the redevelopment of the BDD chawls in the Bombay High Court, writing for the Economic and Political Weekly (EPW), critiquing policies that benefit land owners and developers at the expense of the poor.

Below is an edited interview with him:

You have dedicated yourself to city planning for decades. How has Mumbai changed over the years and what do you make of it?

Mumbai has changed for the worse. Somewhere along the way we lost interest in doing what is best for people. All planning in the suburbs was taken over by developers and the government took no care to ensure high standards and reasonable policies.

Likewise, we lost the 600 acres of mill land in the middle of the city. There could have been east-west links, wider roads, transit systems, etc, but instead they were handed over to the mill owners to develop them as they pleased, without a companion demand for public infrastructure. Whether it was laziness on the part of the administrators or whether there was too much pressure from the developers, I don’t know. But it damaged the city.

What do you think of Mumbai’s 2014 to 2034 development plan?

It is impossible to plan for a city’s needs in 2034 in 2014. You can put your most intelligent minds into thinking 20 years ahead, but they will be defeated by reality. That kind of planning is the legacy of the British. They abandoned it 70 years ago.

Just as we have the Constitution of India, we should have a city charter declaring what we want our city to be. It can include things like having toilets, guaranteed water supply and guaranteed garbage collection for everyone. If a project or policy contravenes the city charter, we should be able to challenge it in court.

The projects and policies that will advance this charter can be reviewed every two or three years at two levels. One is the strategic level, where city leaders deliberate on amenities like transit systems, water supplies, sewerage, etc. And the second level can deal with floorspace index (FSI), footpaths and so on. Leave that to the local ward, who can decide after consultation with the community.

Read more: Has urban planning in Mumbai failed?

Your PIL has challenged the manner in which the BDD chawls are being redeveloped. Could you tell us more about that?

Families that live in a 160 sq ft house with common toilets will be rehabilitated to free-of-cost 500 sq ft apartments. These are being subsidised by adjacent housing built for sale.

Construction cost is around Rs 30,000 sq m, and according to the ready reckoner, the selling price of flats and offices in Worli is Rs 3 lakhs per sq m. That is a 10 fold increase. If 10 floors are being built for rehab, only one floor, 10%, needs to be for sale.

But MHADA is giving away 130% of it for sale. Rehab buildings are bound to be closer together, which will restrict daylight and ventilation. This is damaging for the health of those on lower floors. Government land is public land. It should be developed in a manner which is in the highest public interest.

About 120 people have signed a letter to the chief minister in which we’ve argued for an alternative scheme, where the sale component is reduced to 15% to cover the cost of construction, with a little surplus left for profit. It will make for a less crowded and healthier scheme.

Was the pre-1990 model of slum redevelopment where residents came together to build houses with their own funding better?

Yes, definitely. Schemes of self-financing work if land is given to the people for free or at a nominal charge. The cost of construction of a 500 sq ft apartment in BDD chawls would be about 15 lakhs. People can afford that with a housing loan. What they cannot finance is the land and profit cost, which is nine times that number.

What are your thoughts on Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana?

PMAY only subsidises house ownership, not rental. It subsidises the cost of construction by Rs 2.5 lakh, but a 250 sq ft house costs between 7 to 10 lakhs. While it is a contribution, people will still need housing loans for the balance.

Instead we could have rental housing vouchers, like many countries do. Landlords would get near-normal rents, and a family can choose a house where they can afford the difference between the rent and the housing voucher.

How has the rent control act played out in Mumbai?

It has destroyed Bombay. Immediately after the WW, more than 90% of the houses in Bombay were on rent. With the rent control law, it has come down to 20% of the total. It has made it possible for many of the poor to continue living in high value localities for very low rents. But that has caused all kinds of distortions. No one has built any rental housing, and that’s what makes the city unaffordable for so many.

It’s a hugely damaging Act and it’s time we make construction of housing for renting a viable proposition, something an individual or corporate would be interested in because it has adequate returns.

Will tiny houses create vertical slums?

Vertical slums arise not because of the size of houses, but because buildings are packed too closely together. Mumbai has abandoned all planning norms to do with the ratio between height to open space width.

Read more: A walk around Lallubhai Compound shows what authorities forget before rehabilitating families

The distance required between two buildings is nine metres, just enough for fire engines to pass through. But the height can be infinite. The lower floors have no ventilation or light—it’s like living at the bottom of a well. There are clear reports of the increase in incidence of tuberculosis, as well as new drug resistant strains, in Lallubhai and Natwar Parekh Compounds.

Do you see an inherent problem in small housing?

A small 250 sq ft house is viable only for a family of two or three. Beyond that, it’s not comfortable. But what’s more important is to have a private toilet, adequate light and ventilation.

Is high density a problem at all?

High density is only damaging if it is achieved at the cost of amenities—parks, schools, hospitals, connectivity, shopping areas, etc. Housing is not just a house, it’s everything else around it.

The surroundings need to be liveable. But if you preserve amenities, we should not be scared of high rises.

Why do Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) projects fail to take into account these necessities?

The government sets targets for housing to be built. Their objective is to provide constructed housing, not liveable housing.

Do you think the city’s FSI rules are to be blamed for the state of Mumbai’s housing infrastructure?

FSI has been damaging, because the government has abandoned all other planning parameters for it. But FSI means different things in different situations.

An FSI of 2 with 250 sq feet apartments versus with 2,500 sq feet apartments will give vastly different types of housing. The floor area will be the same, but in the first case it will be shared by ten times the number of people in the larger apartment.

Read more: How Floor Space Index, or FSI, affects housing in Mumbai

Mumbai has an FSI of 1.33, while Manhattan has an FSI of 15. But the average size of an apartment in Mumbai is 250 sq ft, occupied by 5 people; in Manhattan, it is 1,000 sq ft with 2 people residing. If you convert these numbers, you’ll find that the FSI is equivalent.

New York also only allows high FSI with strict conditions, like a minimum apartment size of 4,000 sq ft. The number of people living in an area—density—is kept consistent.

How did you use FSI in the plan for Navi Mumbai?

Because CIDCO owns the land in Navi Mumbai, the idea was that FSI would vary across the city. Higher FSI around stations would mean higher density, so more people are within walking distance of a transport node, like a railway station. People who live in bungalows would live farthest away. This also makes the cityscape more interesting.

Navi Mumbai ended up with a uniform flat FSI of 1 (like Mumbai), after I left the job of planning chief.

What are your thoughts on Mumbai metro?

The metro system is excellent in increasing transit capacity, but it doesn’t open up any new land. The line 3 that goes from Colaba to SEEPZ ends in a car shed in Aarey. It can very well extend east towards Navi Mumbai instead. Navi Mumbai was supposed to move development from the old city towards the new city. That helps the old city as well by keeping population as well as the construction numbers down.

But developers and politicians have a strong interest in keeping the property costs in Mumbai high. They can’t do the same in Navi Mumbai because CIDCO owns the land there. So they are careful that the connections to Navi Mumbai do not happen. Why has the bridge across Thane Creek been dragging on for 20 years?

Are exclusive bus lanes possible in Mumbai?

You can’t destroy much and rebuild in Mumbai. But it is possible in a new area like the airport authority in Navi Mumbai, or through the redevelopment of the Mumbai Port Trust’s Eastern Waterfront.

There should be two separate networks—roads and transit. The two should never intersect. One should go above or below the other. The railway works well at high speeds because it has an exclusive track. Buses would work well if certain roads are exclusively reserved for them.

What do you think of the coastal road project?

The Coastal Road Project is meant to serve people who are travelling on the western edge of Mumbai. These will be wealthy people in cars, going from home to office, to club, to hotels.

There’s a clear class segregation; the poor will live on the eastern side and serve those on western side.

This interview was conducted as part of a series of articles on Urban Planning in Mumbai, supported by a grant from the A.T.E. Chandra Foundation.